Torn Between Expectations and Imagination: Alternative Forms of Communicating Educational Research

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 2 Abstract

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 1 This paper is based on a workshop delivered at the 2015 Annual Kaleidoscope Conference, with an aim to introduce as well as inspire ways of communicating educational research in creative ways. We start with an overview of the theoretical frameworks and our rationale. We then discuss alternative approaches to communicating educational research and how these are informed by arts-based methodologies and practitioner research. After a short description of the workshop (how it was structured and run and its outcomes), we proceed to present our reflections, and suggest possible directions for future research concerning the imperative of communicating academic research to a wider audience. The workshop was successful in terms of stimulating participants to think about the challenges of presenting research to different audiences as well as enabling them to explore and reflect upon possible approaches. Nonetheless, we believe that further research is needed to examine and address the tension between forms of reporting and presenting research that are generally accepted and celebrated in academia and the need to present research to different audiences using different styles. We argue that researchers can be more proactive in affirming the value of alternative forms of presenting research and seeking support from both within and outside their institutions. We also foresee the prospect of more collaborative and participatory models of presenting research, along with further reflexive critique of the established framework of reporting and communicating academic research.

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 Keywords: communicating educational research; alternative ways, arts-based research, practitioner based research

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 Introduction

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 1 This paper is based on a workshop that we delivered on May 28th, 2015 at the Kaleidoscope Conference at Cambridge University 2015: Many Paths, Same Goal—Multimodality in Educational Research. The main aim of the workshop was to explore alternative methods of presenting academic research through discussion and group work. The workshop originated from our common interest in communicating research in creative and effective ways. With the goal of delivering an exploratory, experimental, collaborative and participatory workshop, we structured it in such a way as to leave time and space for all participants to try out ideas in groups.

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 1 We facilitated and observed the teamwork that took place. Given the time limit, only a few participants had the chance to express immediate reaction, during the discussion section at the end of the workshop. Based on our desire to write a first iteration based on fresh memories, we published a short reflective paper online[1] five days after the workshop. By doing so, we were able to retain our immediate thoughts whilst we hoped that our ideas could possibly generate further discussion. This article is based on our original reflective paper, but in addition the four-month gap has allowed us to add another layer of reflection and further contemplate on the implications of the workshop.

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 1. Perspectives from Arts-Based Methodology and Practitioner Research

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 1 As a novice researcher, Yanyue’s doctoral research explores visitors’ imaginative responses towards cultural objects in museums. To tap into the subjective, fleeting and ineffable nature of imagination, Yanyue integrated poetic writing into her research, inspired by arts-based methodology. James has had rich teaching experience in schools and his research has been largely influenced by his teaching background. He has worked extensively with teacher researchers and also with practitioner researchers in other professions. James is interested in the potential that reflective and arts-based methodologies have for bridging the gap between academic research and practice.

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 1.1 Arts-Based Methodology

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 2 Arts-based methodologies only began to emerge in the field of education in the 1980s. The term “Arts-Based Educational Research” (ABER) was officially used in 1993 when Elliot Eisner, together with his graduate students, proposed the idea to members of the American Educational Research Association at the Arts-Based Research Institute, Stanford University (Barone & Eisner, 2011; Cahnmann-Taylor, 2008; Eisner, 2006). The fundamental belief of ABER is that “the arts have the ability to contribute particular insights into, and enhance understandings of phenomena that are of interest to educational researchers” (Donoghue, 2009, p. 352). Within the last two decades, many experimental and exploratory efforts have been made to integrate features of arts-based methodologies in educational research, especially in the stage of communicating research.

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 A wide range of art forms have been employed in research, including poetry, fiction, music, visual arts, exhibition, drama and other types of performances. For example, during a session at the annual conference of the American Educational Research Association (AERA) in 1997 a group of researchers performed their ethnographic data, which culminated in a collection entitled “Dancing the Data”. Their work was published in a book accompanied by a CD-ROM that documented the performative presentations. The book exemplifies how stories collected in educational research can be transformed into music, drama, poetry, dance and other artistic performances. More recently, Leavy (2013) makes a case for fiction as research practice and maps out various ways of creating fiction to synthesise and present research data. Doctoral students have also been actively trying out new methods and experimenting with new ways to present their work. One example is Loi’s multimedia PhD thesis (2005) displayed in suitcases (containing her abstract, papers, CDs, artworks, objects, etc.). Corresponding to her thesis topic of collaborative design tools and methods, the suitcases were made to encourage participants to join the participatory design activities.

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0 1.2 Practitioner Research

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 1 Practitioner research is a type of research that is deeply grounded in the practicalities of the workplace. The simplest definition of practitioner research is that it is research conducted by people who also work within the profession and context that they are researching (Taber, 2013). This may be teachers conducting research into their own teaching or that of their colleagues although it could refer to any professional conducting research into their own context. Practitioner research has an established history, yet still to some extent sits outside the conventional academic discourse. This history includes the dominance of an action research paradigm in the 1980s (McNiff, 2013) and the development of this further into nuanced but related forms, such as research conducted within the framework of non-positional teacher leadership (Frost, 2008). However, there is also research conducted by practitioners which is positioned as ethnography, case study or auto-ethnography. Therefore, practitioner research is a term which spans across a range of methodological positions (Taber, 2013).

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 1 The term practitioner research is useful though, as almost all practitioner research tends to have significant commonalities, which include an acknowledged subjectivity on behalf of the researcher and a goal of achieving a concrete change in classroom or workplace strategy for oneself and for one’s colleagues (Frost, 2015). Methods of dissemination are also distinct and sit outside usual academic conventions. These modes of dissemination may be via forms of workplace communication: training days, internal or semi-formal publications or forms of peer support and mentoring. Non-conventional forms of dissemination may therefore help to break down the barriers between practitioner research and the conversations that take place in the university-based academic world.

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 1 2. A Brief Overview of the Workshop

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0 The workshop was divided into three parts, which can be briefly termed as: orientation, group work, and reflection.

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0 The focus of the workshop lay in the interactive group work. Participants were asked to produce a group presentation and were given 20-minutes of preparation time to do so, based on the following rules:

- ¶ 18 Leave a comment on paragraph 18 1

- The “project” must incorporate (at least one element of) each group member’s research (suggestions included: research topic, methodology, theoretical framework, range of participants);

- It must involve the “object” that the group were given (by any creative means that the group decided on);

- Presentation must be within two minutes;

- It needed to be in the form of a Play or Poem or Picture.

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0 Yanyue brought a bag of random objects to the workshop (including a number of everyday and curious objects, e.g., beach shell, necklace, bookmark, key ring). We hoped that the objects could serve as a creative stimulus to inspire free association and creative approaches. A representative from each group was invited to draw an item out of the bag of objects. Before the group work began, we stressed the importance of bearing in mind our audience when we communicate our research. We thus encouraged the participants to describe their intended audience when presenting their project.

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 2 The 15 participants were mainly attendees of the conference (along with a few research staff at the faculty), most of whom were postgraduate research students in the UK. The participants were split into three groups of five, with each group sitting around the same table. Each group had a few materials to assist their preparation and presentation, including: coloured poster paper, colouring pens, scissors, and glues. As workshop facilitators, we observed how things went on and approached each group to make sure that they understood the task (see Figure 1).

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0

¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0 Figure 1. Participants begin to work as a group

¶ 23

Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0

¶ 24 Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0

¶ 25 Leave a comment on paragraph 25 0

¶ 26 Leave a comment on paragraph 26 2 The atmosphere was positive, but during the first few minutes a number of participants told us they found it challenging to identify a particular way of including everybody’s research and deciding on the exact form of presentation. Once this had been resolved, all groups delved into heated discussions in order to prepare for the presentation of a presentable piece.

¶ 27 Leave a comment on paragraph 27 0

¶ 28 Leave a comment on paragraph 28 0 Figure 2. Groups delve into brainstorming

¶ 29

Leave a comment on paragraph 29 0

¶ 30

Leave a comment on paragraph 30 0

¶ 31 Leave a comment on paragraph 31 0

¶ 32 Leave a comment on paragraph 32 0

¶ 33 Leave a comment on paragraph 33 0 2.1 Description of Three Group Presentations

¶ 34 Leave a comment on paragraph 34 1 As it is difficult to re-enact the presentations in textual form given their performative nature, we have illustrated each group’s presentation through photos. The following summary is a descriptive account illustrated by seven photos. In this section we have kept our comments and interpretation to a minimum, as this gives the reader a better idea of what came out of the workshop.

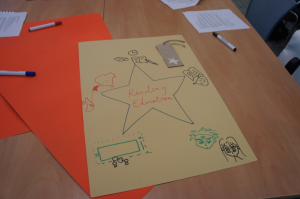

¶ 35 Leave a comment on paragraph 35 1 2.1.1 Group One: A Research Proposal around a Five-Pointed Star

¶ 36 Leave a comment on paragraph 36 0

¶ 37 Leave a comment on paragraph 37 0 Figure 3. Group One’s poster

¶ 38

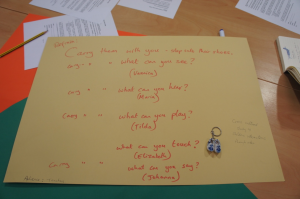

Leave a comment on paragraph 38 0

¶ 39 Leave a comment on paragraph 39 0

Group One demonstrated their object: a brown bookmark illustrated with a white five-pointed star. Their intended audience was colleagues within the academic community.

¶ 40 Leave a comment on paragraph 40 0 Inspired by the five-pointed star on the bookmark, Group One designed a collaborative research project into a comparative study of young people’s reading experiences of Japanese manga in China and the UK. Together, they drew a poster with a big five-pointed star in the middle, with five elements at each corner.

¶ 41 Leave a comment on paragraph 41 0

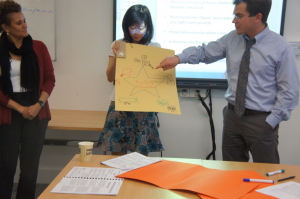

¶ 42 Leave a comment on paragraph 42 0 Figure 4. Group One demonstrating their poster

¶ 43

Leave a comment on paragraph 43 0

¶ 44 Leave a comment on paragraph 44 0

¶ 45 Leave a comment on paragraph 45 0 2.1.2 Group Two: A Song for Children

¶ 46 Leave a comment on paragraph 46 0 The object that Group Two obtained was a key ring, featuring a small pair of ceramic shoes. They prepared a poetic song, with the phrase ‘Carry them with you, step into their shoes’ as the chorus. They explained that since most of them were working with children in their research, they hoped to bring the children’s perspective into their presentation. The presentation itself was dedicated to children who were their imaginative audience.

¶ 47 Leave a comment on paragraph 47 0 Figure 5. Group Two’s object and their notes

¶ 48

Leave a comment on paragraph 48 0

¶ 49 Leave a comment on paragraph 49 0

Each group member started with the chorus ‘Carry them with you step into their shoes’, followed by their answers to one of the following questions that the rest of the group members posed:

- ¶ 50 Leave a comment on paragraph 50 0

- What can you see?

- What can you hear?

- What can you play?

- What can you touch?

- What can you say?

¶ 51 Leave a comment on paragraph 51 0

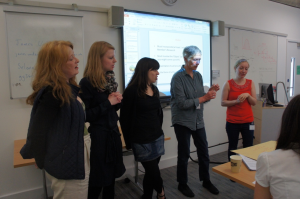

¶ 52 Leave a comment on paragraph 52 0 Figure 6. Group Two presenting their song

¶ 53

Leave a comment on paragraph 53 0

¶ 54 Leave a comment on paragraph 54 0

¶ 54 Leave a comment on paragraph 54 0

¶ 59 Leave a comment on paragraph 59 0

¶ 55 Leave a comment on paragraph 55 0 2.1.3 Group Three: A Gift to My Teacher

¶ 56 Leave a comment on paragraph 56 0 Group Three presented a short play, and used their object—a red necklace—as the key prop. Their intended audience was students and teachers.

¶ 57 Leave a comment on paragraph 57 0 The main plot of their play went as follows:

¶ 58 Leave a comment on paragraph 58 0 The protagonist, a young female student, had just received a birthday gift from her mother: a necklace that the mother bought during a trip. She expressed the idea of giving the gift to her teacher, to whom she was truly grateful. Her mum agreed and thought it was a good idea. She then met her classmates on her way to school and they all sent her birthday wishes and encouraged her to do so. After the class, she gave the gift to her teacher and expressed her gratitude by giving her a hug.

¶ 80 Leave a comment on paragraph 80 0

¶ 60 Leave a comment on paragraph 60 0 Figure 7. Group Three’s object and a scene from their short play

¶ 61

Leave a comment on paragraph 61 0

¶ 62

Leave a comment on paragraph 62 0

¶ 63 Leave a comment on paragraph 63 0

2.2 Concluding Reflections

¶ 64 Leave a comment on paragraph 64 1 We reserved ten minutes towards the end of the one-hour workshop for discussion. We invited all participants to talk about the challenges of this group work and what they enjoyed most. Given the time limit, not all participants had the chance to speak about their experience. Most of the participants who did speak, however, considered the collaborative element to have been the biggest challenge. They mentioned the difficulty of working out a group presentation within twenty minutes. On the other hand, they were surprised by their productivity. Some participants mentioned how they were inspired by what they had experienced during the workshop and would consider alternative forms of presenting and communicating their own research in the future.

¶ 65 Leave a comment on paragraph 65 0 3. Reflective Remarks

¶ 66 Leave a comment on paragraph 66 1 As we mentioned, we wrote an informal reflective paper shortly after the workshop. Workshops are platforms that inspire and retain collective wisdom. Without other forms of dissemination, our workshop at the conference would only be a short experience recognised by the 15 participants. The one-off experience may soon fade away and the learning experience could not be taken much farther. Schön (1983) has critically challenged the “dichotomy of thought and action” (p. 280) and she calls attention to “reflection-in-action” that entails “the outcomes of action, the action itself, and the intuitive knowing implicit in action” (p. 56). The value of “reflection-in-action”, however, can be supplemented by “reflection-on-action” and the time gap between “action” and “reflection” can help freshen our perspectives. Therefore, this paper edited four months after the workshop further crystalizes our ongoing reflections.

¶ 67 Leave a comment on paragraph 67 0 First and foremost, the workshop reaffirmed our belief in the diverse choices and opportunities that academic researchers have when communicating research. As academics we need an audience for our work and we need to know who this audience may be. However, we can often find it hard to picture who we are writing for. Presenting our work to varied audiences can enable us to find multiple audiences and therefore can make the long journey to formal publication in a journal or the production of an examined thesis more tolerable. The process of trialling alternative ways of presenting research can bring multiple benefits:

- ¶ 68 Leave a comment on paragraph 68 1

- When choosing a method for presentation to an alternative audience, we often need to avoid complex language, which demands us to clarify thoughts and synthesise arguments. For instance, trying to explain one’s thesis or article to children in a way that they will follow can be a challenge as well as an opportunity to learn how to communicate our theories and findings in more engaging and creative ways.

- Alternative forms of publication or dissemination often require collaboration, which can reduce the risk of being too isolated as researchers as a result of needing to find a space of our own to write. Collaborating with our colleagues and those outside the academic community can help us to establish social relations that can add dynamism to our academic research experience.

¶ 69 Leave a comment on paragraph 69 0 The theme of collaboration seemed to emerge as another implicit aspect of workshop. One participant commented that trying to explain everyone’s research in a very short period of time was almost like an “academic speed-date.” Considering the busy schedule of people working in other sectors, we believe academics now need to seriously consider honing our abilities at communicating our own research to other people and making ourselves understood within a limited time.

¶ 70 Leave a comment on paragraph 70 1 In addition, the workshop itself exemplified the capacity for learning by doing. Without the group exercise, we might find it extremely hard to articulate what we mean by the potential for communicating research in alternative forms. With the group exercise, the participants could have a real experience of what it might be like when they needed to communicate their research in ways other than those forms that they were familiar with. The exercise was a prompt that might stimulate further thinking about the rationale, consequences and challenges around communicating academic research in various ways to different audiences.

¶ 71 Leave a comment on paragraph 71 0 The workshop inspired us to think carefully about the tensions that exist when thinking about alternative ways of presenting research. To deal with our concerns, we believe that we need to take initiatives to build up our confidence and to take steps in celebrating and encouraging such possibilities. We tend to often prioritise written reports as the most legitimate form of dissemination. This is most likely inculcated in us by the current accountability culture in higher education in terms of judging and assessing academic research for defining excellence and distributing funding. However, we can already discern an increasing awareness of the wide range of approaches towards “publishing” research. In the UK, the Research Excellence Framework (REF) is the nationwide system for assessing the quality of research in all UK higher education institutions. The most recent document published on the REF website on guidance and submission states explicitly that the system takes into account various forms of academic work:

¶ 72 Leave a comment on paragraph 72 0 In addition to printed academic work, research outputs may include, but are not limited to: new materials, devices, images, artefacts, products and buildings; confidential or technical reports; intellectual property, whether in patents or other forms; performances, exhibits or events; work published in non-print media (REF, 2011, p. 22).

¶ 73 Leave a comment on paragraph 73 0 What remains to be explored is: Should we apply different criteria when assessing research output in different forms? To what extent are conventional written forms be given more credit considering the implicit hierarchy of forms of research dissemination? Following this inquiry, why? Should this be changed?

¶ 74 Leave a comment on paragraph 74 1 As researchers, we might also be caught up in our habitual thinking of confining our academic achievements within academic papers. We suggest that a critical attitude should be adopted to challenge the embedded hierarchy. We might, for example, celebrate our output in forms of photographs, or poems, or performances on our academic CV, as we can often dedicate equal, if not more, effort and time to such creations. Collectively, our celebrative stance might help to initiate a paradigmatic change. Meanwhile, reflecting on our own efforts in making a case for this initiative, we want to call for further support within higher education to offer guidance to research students and even research staff. We would argue that just as novice researchers need practice and guidance when learning how to write academically, they also need equal, if not more, support when it comes to presenting our research through a diverse range of channels.

¶ 75 Leave a comment on paragraph 75 0 4. Implications

¶ 76 Leave a comment on paragraph 76 0 In this paper, we have introduced our research background and the theoretical frameworks underpinning our design of the workshop. We reviewed the structure and the main content of the workshop, including the outcomes of the group work. Most importantly, we reflected upon the nature of the workshop itself and the challenges that researchers need to overcome when communicating research in forms other than the written academic paper. We encourage researchers to take on a more positive attitude towards alternative forms of expressing ideas and actively seek help and support. While we acknowledge the importance of ensuring the quality of academic research by means of learning to report our research in academic writing, we also believe that the world is rapidly changing. There are significant pressures for the academic community to engage in this wider world and to ensure that the wider professional world engages with us.

¶ 77 Leave a comment on paragraph 77 1 Both the workshop and this paper conform to our philosophy that the purpose of publishing research is for generating dialogue rather than simply reporting one’s own thought or achievement. Our ideas are situated in scholarly discussions over the role of higher education institutions. Researchers have called attention to the importance of examining and improving the ‘engagement model’ of universities (Furco, 2010; Weerts, 2007; Weerts & Sandmann, 2010) as higher institutions need to address civic duty and transparency. At a macro level, Byrne (2000) argues that universities “are critically important to the development of civil societies” (p. 16). Moreover, a responsibility for considering the needs of our audiences and participants is a crucial ethical element. In this paper, we have argued that alternative arts-based forms of dissemination and publication can be one type of effort towards enriching and varying academic conversations. At the same time, these endeavours can simultaneously provide a reflective space, demanding us to experiment, practise and improvise ways of articulating and presenting our research to different audience on different occasions.

¶ 78 Leave a comment on paragraph 78 1 In the long run, we believe that this new agenda would demand an accompanying set of criteria for judging the quality of different forms of presentation. This would, arguably, prompt us to think about the hierarchy within research institutions. Take Group Two’s reflections for example, how and to what extent can we rely on children’s perspectives and comments when our research is about children? What role(s) can children and will children be allowed to play when judging the presentation of the research outcomes based on their experience? This leads us to a paramount mission, as communicating research would then indicate the launch of relational and responsible communication. Our workshop has only touched upon a small corner of the vast territory of communicating research in alternative forms. We believe that our effort has, to some extent, proved the worthiness and urgency of further exploration into this theme.

¶ 79 Leave a comment on paragraph 79 0 It is noted that the current climate in higher institutions does not seem to be in full support of the engagement mode (Driscoll & Sandmann, 2010). The agenda of further fostering engagement and collaboration requires us to creatively tackle challenges at different levels. Enders (2005) proposes that PhD training needs to move from “an academic-disciplinary model” to “a hybrid model that crosses disciplinary and organizational borders” (p. 119). For individual researchers, we want to suggest the following two imperatives: (a) seeking and ensuring collaboration with research participants as well as those whose life might be influenced by our research. This would mean shifting the top-down dissemination model into a collaborative and participatory framework during the stage of presenting academic research; (b) further deconstructing the established status of academic writing and firming up the ground of creative forms of conducting and communicating research by reinvigorating practice-informed theory. We share Byrne’s (2000) optimistic prediction that engagement will be a defining characteristic of the university of tomorrow, and we are aware that this requires courage, creativity, a caring attitude, and intellectual input.

¶ 82 Leave a comment on paragraph 82 0

¶ 81 Leave a comment on paragraph 81 0 Acknowledgements: We would like to thank all the participants at the workshop who actively engaged in the group activity and contributed their thoughts. We are also grateful for their consent to photo taking and the inclusion of the photos in publications. We thank our colleague, Ningfen Wang, who kindly offered to take photos some of which are included here as additional resources accompanying this paper[2].

¶ 83 Leave a comment on paragraph 83 0

¶ 101 Leave a comment on paragraph 101 0

¶ 84 Leave a comment on paragraph 84 0 References

¶ 85 Leave a comment on paragraph 85 0 Barone, T., & Eisner, E. (2011). Arts Based research. London, England: SAGE.

¶ 86 Leave a comment on paragraph 86 0 Byrne, J. V. (2000). Engagement: A defining characteristic of the university of tomorrow. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, 6(1), 13-21.

¶ 87 Leave a comment on paragraph 87 0 Cahnmann-Taylor, M. (2008). Arts-based research: Histories and new Directions. In M. Cahnmann-Taylor & R. Siegesmund (Eds.), Arts-based Research in Education: Foundations for Practice (pp. 3-15). New York, NY; London, England: Routledge.

¶ 88 Leave a comment on paragraph 88 0 Donoghue, D. O. (2009). Are we asking the wrong questions in arts-based research? Studies in Art Education, 50(4), 352-368.

¶ 89 Leave a comment on paragraph 89 0 Driscoll, A., & Sandmann, L.R. (2001). From maverick to mainstream: The scholarship of engagement. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, 6(2), 9-19.

¶ 90 Leave a comment on paragraph 90 0 Eisner, E. (2006). Does arts-based research have a future? Inaugural lecture for the first European conference on arts-based research. Studies in Art Education, 48(1), 9-18.

¶ 91 Leave a comment on paragraph 91 0 Enders, J. (2005). Border crossings: Research training, knowledge dissemination and the transformation of academic work. Higher Education, 49(1-2): 119-133.

¶ 92 Leave a comment on paragraph 92 0 Frost, D. (2008). Teacher leadership: Values and voice. School Leadership and Management (Special issue on Leadership for Learning), 28(4), 337-352.

¶ 93 Leave a comment on paragraph 93 0 Furco, A. (2010). The engaged campus: Toward a comprehensive approach to public engagement. British Journal of Educational Studies, 58(4), 375-390.

¶ 94 Leave a comment on paragraph 94 0 Leavy, P. (2013). Fiction as research practice: Short stories, novellas, and novels. Walnut Creek, CA: California Left Coast Press, Inc.

¶ 95 Leave a comment on paragraph 95 0 Loi, D. A. (2005). Lavoretti per bimbi: Playful triggers as keys to foster collaborative practices and workspaces where people learn, wonder and play (Doctoral dissertation, RMIT University, Australia).

¶ 96 Leave a comment on paragraph 96 0 McNiff, J. (2013). Action research: Principles and practice (3rd ed.). London, England: Routledge.

¶ 97 Leave a comment on paragraph 97 0 Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. London, England: Temple Smith.

¶ 98 Leave a comment on paragraph 98 0 Taber, K.S. (2013). Classroom-based research and evidence-based practice: An introduction (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

¶ 99 Leave a comment on paragraph 99 0 Weertz, D. J. (2007). Toward an engagement model of institutional advancement at public colleges and universities. International Journal of Educational Advancement, 7(2), 79-103.

¶ 100 Leave a comment on paragraph 100 0 Weertz, D. J. & Sandmann, L.R. (2001). Community engagement and boundary-spanning roles at research universities. The Journal of Higher Education, 81(6), 632-657.

¶ 102 Leave a comment on paragraph 102 0

¶ 103 Leave a comment on paragraph 103 0

¶ 106 Leave a comment on paragraph 106 0

¶ 104 Leave a comment on paragraph 104 0 [1] We both have our profile pages on researchgate.net and academia.edu. The two sites offer researchers across the world a platform to upload papers, and network with other researchers.

¶ 105 Leave a comment on paragraph 105 0 [2] Consent forms for taking and publishing photos were placed on each table during the workshop and the participants were asked to sign the forms or otherwise indicate their unwillingness to be photographed.

Comment awaiting moderation

Comment awaiting moderation

Comment awaiting moderation

Comment awaiting moderation

Comment awaiting moderation

Comment awaiting moderation

Comment awaiting moderation

Comment awaiting moderation